Most of us will never get a mega-buyout like Scott Frost, but some of us may suffer adverse consequences for standing up for workplace justice like former Nebraska star center, Dave Rimington, did during the 1987 NFL Players’ Strike.

The $15 million platinum parachute received by former Nebraska quarterback and head football coach, Scott Frost — four years of salary with no questions asked after 4 plus years of sub-par job performance is something 99.9999 percent of workers will never experience.

However, another Nebraska football legend had on-the-job experiences that are more common and applicable for the rest of us; Dave Rimington.

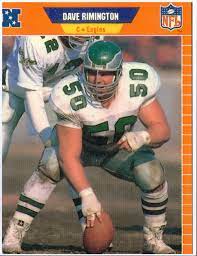

For those of you who aren’t football fans, Dave Rimington was a two-time All American center at the University of Nebraska, two-time Outland Trophy winner who even finished 5th place in Heisman Trophy balloting in 1982. He went on to a seven-year NFL career. The Rimington Trophy for the best college center bears his name.

But this post isn’t about his gridiron heroics, this post is about Rimington’s experience as a union leader during the 1987 NFL players’ strike.

Rimington was drafted by the Cincinnati Bengals in 1983 where he first paired with his now long-time friend quarterback Boomer Esiason. Rimington and Esiason were both Bengals team leaders in the National Football League Players’ Association (NFLPA), the union that represents NFL players.

In 1982, the players staged a moderately successful in strike for better pay and benefits, so they decided to try again in 1987.

Except in 1987, the players strike didn’t succeed. The owners were able to bring in scabs/replacement players to slake the demands of fans for football. Many high-profile players, such as future Hall of Famer Joe Montana, crossed union picket lines.

In short, the owners were able to break the strike.

Rimington faced consequences from the Bengals for his role in the strike. In an article from ESPN/ABC in 2001, Rimington stated he believed the Bengals would not let him return from injured reserve as a result of his activities during the strike. In other words, his employer would not let him return to work after a work injury after engaging in the protected activity of engaging in a labor strike. (Esiason criticized the Bengals’ action at the time in an act of solidarity. He believe it was a false or pretextual reason)

In even fewer words, the Bengals retaliated against Rimington for his union activities. Many less known and lower-profile employees have faced the same situation.

And like other employees facing employer retaliation, their employer may have had some plausible excuse to discipline Rimington. According to press reports from the time, Rimington was videotaped keying the car of a scab/replacement player. The Bengals fined Rimington for that alleged misconduct. Again, some employee misconduct doesn’t always defeat an employee retaliation claim, but the broader point is that even imperfect employees can assert their rights in the workplace.

From reports at the time, Rimington expressed regret at the outcome of the strike. Not every employee who stands up to their employee gets a Hollywood ending. But nonetheless, some employees do get positive outcomes when they stand up for themselves on the job – either individually or collectively through their union.

Further, employees do win strikes sometimes. One example is the strike at Kellogg’s last fall. Sometimes even the credible threat of a strike can win concessions from employers as could be the case with a potential railway labor strike where the parties have reached a preliminary agreement. Even a failed strike like the 1987 NFL Players strike can give lessons about how to succeed in the future if people are willing to study history. But there is no history unless people are willing to act. Former Husker Dave Rimington was one of those who were willing to act during the 1987 NFL players’ strike.